Predictive Embodiment

Understanding the embodied intelligence by which the human person actively anticipates, reveals, and co-constructs personal identity and relational meaning

Introduction

In contemporary thought, human experience is increasingly understood as active and predictive rather than passive. From neuroscience to philosophy and theology, scholars are converging on the idea that the mind-brain anticipates and constructs our reality. This article explores an interdisciplinary synthesis of three seemingly disparate frameworks – Bernard Lonergan’s cognitional theory, Lisa Feldman Barrett’s neuroscience of interoceptive prediction, and Pope John Paul II’s Theology of the Body – to illuminate a richer understanding of embodiment. We propose that experience is inherently predictive, and that the body actively anticipates and shapes personal identity through an embodied cognitive–affective loop. By integrating Lonergan’s account of how we know, Barrett’s model of how the brain constructs emotion, and John Paul II’s teaching that “the body reveals the person,” we will see that the body might even be said to “predict” the person – actively participating in revealing and constituting who we are. In what follows, we outline the foundational theories of Lonergan and Barrett (identifying their conceptual overlaps), explain how interoceptive predictions shape our lived narrative, offer a theological reframing of John Paul II’s insight (“the body reveals the person”) in light of predictive embodiment, and consider the ethical and relational implications of this perspective. Along the way, connections with cognitive science, phenomenology, and philosophy will be drawn, and real-world examples will illustrate how predictive embodiment plays out in psychology, education, and human development.

By the end, we aim to show that integrating these frameworks not only advances academic discourse but also provides practical wisdom: understanding ourselves as predictively embodied persons can enrich empathy, inform moral responsibility, and deepen our appreciation for the mysterious interplay of body, mind, and spirit in personal identity.

Overview of Lonergan and Barrett: Active Cognition and Predictive Affect

Bernard Lonergan’s Cognitional Theory: Lonergan, a 20th-century Jesuit philosopher-theologian, developed a detailed account of “what we do when we know.” In his works Insight (1957), Verbum, and Method in Theology (1972), Lonergan portrays human knowing as a dynamic, structured process with distinct levels. Rather than a passive recording of sense impressions, knowing for Lonergan is an unfolding self-transcending process. He identifies four levels of consciousness: (1) Experience – the empirical level of sensing, perceiving, and feeling data; (2) Understanding – the level of insight, where we inquire and grasp patterns or intelligible forms in the data; (3) Judgment – the reflective level, asking “Is it really so?”, where we weigh evidence and affirm what is true; and (4) Decision – the level of choosing and acting based on values and truths known. Each level builds on the previous and comes with its own intrinsic norm (e.g. be attentive at the level of experience, be intelligent in understanding, be reasonable in judgment, be responsible in decision). Notably, experience itself is not a brute, neutral reception of stimuli; it is “prepatterned” by attention – our interests and needs guide what we notice. Lonergan points out that at the experiential level our consciousness shifts among various “interests” (biological, practical, aesthetic, intellectual, etc.), priming us to notice some data over others. In other words, even our sensory experience has an implicit orientation or anticipatory structure governed by our underlying drives and concerns.

Lonergan also gives special emphasis to the role of questions in cognition: the mind’s unrestricted drive to know propels us beyond what is given, raising questions that lead to insights. An insight, as Lonergan famously explains, is not just a visual “picturing” but a leap beyond images to grasp a pattern or solution. This means human understanding inherently involves reaching toward the as-yet-unseen. There is a built-in heuristic (or anticipatory) element – our questions set up an expectation or leading clue that guides the insight. Thus, for Lonergan, knowing is in a sense actively exploratory and prospective. Human knowing always begins in media res – we start from experienced data, but that experience is already informed by our interests and followed by inquisitive insights that go beyond the data to hypothesize what could be.

Crucially, Lonergan does not ignore the role of the body and affect in this cognitional enterprise. In Method in Theology, he analyzes how feelings and affectivity interlace with our intellectual operations. Feelings, far from irrational epiphenomena, perform a double function: as “operators”, they are impulsive clues that provoke us to ask questions or seek value (a feeling of curiosity or awe spurs inquiry, a feeling of disgust or empathy prompts moral questioning); as “integrators”, feelings become woven into our psyche as enduring orientations that smooth our interactions. For example, over time our affective responses get linked with images and values into subconscious “symbols” that orient our view of the world. These affective–image symbols help us respond “smoothly without having to reassess everything at every moment”. In other words, we develop an implicit framework of expectation (a pre-set way of feeling-and-seeing situations) that streamlines our engagement with life. Lonergan is effectively describing a kind of internal model shaped by past experiences and feelings – a notion strikingly consonant with what today’s neuroscience calls predictive processing. He also acknowledges how such affect-laden schemas can bias us (for good or ill) and need conversion to align with true value. Overall, Lonergan’s theory presents human knowing as embodied, dynamic, and oriented by anticipation: from the selective spotlight of attention and the questions that drive understanding, to the feeling-toned symbols that quietly guide our perceptions and choices, the human subject is always actively structuring experience in dialogue with the world.

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s Neuroscience of Interoceptive Prediction: Barrett, a leading contemporary neuroscientist and psychologist, offers a compatible yet more empirically grounded perspective on how we construct experience – particularly our emotional life – through the body–brain dialogue. Barrett’s Theory of Constructed Emotion posits that the brain is fundamentally a prediction engine, and that what we experience (especially as emotion) is the result of the brain’s interpretation of sensory inputs (both external and internal) through the lens of past experience and concepts (Theory of constructed emotion - Wikipedia). In Barrett’s view, raw sensations (such as changes in heart rate, breathing, or external percepts) don’t come with built-in meaning. The brain must make sense of them, and it does so by using memory and concepts to guess what the sensations signify and what to do about them. This inferential process happens at lightning speed and largely outside of conscious awareness. Crucially, Barrett emphasizes interoception – the sensing of internal bodily states (like hunger, pain, arousal, etc.) – as a primary input to this constructive process. The brain issues predictions about the body’s internal needs and upcoming states (what Barrett calls allostasis or body budgeting) and compares incoming sensory data against these predictions (Interoceptive predictions in the brain - PubMed) ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). Rather than the body simply sending up signals that the brain then feels, “interoceptive experience may largely reflect limbic predictions about the expected state of the body, constrained by ascending visceral sensations.” (Interoceptive predictions in the brain - PubMed) In plainer terms, your feeling of say, anxiety or calm, is not a direct readout of your body but your brain’s best guess of what bodily sensations mean, based on context and history, adjusted by the actual sensory inputs.

Barrett’s research (summarized in works like How Emotions Are Made and articles on Embodied Predictive Interoception) provides many examples: “In every waking moment, your brain uses past experience, organized as concepts, to guide your actions and give your sensations meaning… When the concepts involved are emotion concepts, your brain constructs instances of emotion.” (Theory of constructed emotion - Wikipedia) Thus, if your heart is pounding and stomach fluttering, your brain might construct “anxiety” if you’re about to give a speech, or “excitement” if you’re about to meet a loved one – the physiological data on its own is ambiguous, but the brain’s predictive coding resolves it by imposing an interpretation. These interpretations are not arbitrary – they draw on our embodied history (culture, language, prior learnings). Barrett notes that interoceptive predictions culminate in core affective feelings (valence and arousal – feeling pleasant/unpleasant, energized/sluggish), which our brain then categorizes into discrete emotions using learned concepts and social cues. Even our perception of something as basic as color is used as an analogy: just as the brain carves up a continuous spectrum of light into categorical colors like “blue” or “red” based on learned categories, so it carves up a continuous flux of bodily affect into emotions like “anger” or “joy” via predictive concept-matching.

Central to Barrett’s neuroscience is the principle that the brain is geared toward efficient regulation of the body’s needs. She highlights the concept of allostasis, meaning maintaining stability through change. Instead of waiting for deficits (e.g. lack of glucose or oxygen) to occur and then fixing them, the brain tries to anticipate needs and prepare in advance ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). “Allostasis is a predictive balancing act… your brain is engaged in the constant body-budgeting of allostasis, anticipating your body’s needs at every moment while deciding which efforts are worth the metabolic investment.” ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). For example, as you read this paragraph, your brain is budgeting energy for concentration; if you suddenly stand up, your brain will have already predicted the need to increase blood pressure to prevent dizziness ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). This budgeting occurs by way of predictions: the brain issues commands to bodily systems and simultaneously predicts the sensory outcomes (e.g. what blood pressure or heart rate should result) ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). When the incoming signals match the prediction, the brain “feels” all is well; if there’s a mismatch (prediction error), the brain updates its model or adjusts the body. Notably, exteroception (sensing the outside world) works in a similar predictive manner: “Exteroception works mostly by prediction. Your brain issues motor commands… and simultaneously predicts the sensations likely to result… When the actual sense data arrives… your brain integrates the data to confirm or correct the predictions.” ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). In short, whether perceiving the external world or the internal milieu, the brain operates on a predictive coding paradigm – constantly pre-construing what inputs mean and fine-tuning its beliefs based on the feedback it gets.

Conceptual Overlap: Despite their different starting points (one philosophical and cognitional, the other neuroscientific and affective), Lonergan and Barrett share key insights about the active, constructive nature of human experience. Both reject a naive empiricist model where the mind is a passive mirror of reality. Instead, experience is portrayed as an ongoing interaction between incoming data and internal anticipatory structures. For Lonergan, the mind has an eros of inquiry – a driving desire and internal norms that reach out for patterns and value, effectively meaning our consciousness is always leaning forward (wondering, expecting intelligibility) beyond the given. Our attention is filtered by biological and existential interests, and our accumulated insights and affective symbols bias how new experiences are assimilated. This resonates strongly with Barrett’s finding that the brain’s default is to guess first, verify later – using past experience to impose meaning on sensations, then checking against reality ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). Both accounts emphasize feedback loops: Barrett’s brain continually checks prediction against sensation (updating or reinforcing its internal model), and Lonergan’s knower moves from experience to understanding to judgment and back again, refining insights against new data and higher viewpoints (in scientific discovery, for example). There is also a common recognition of the integration of cognition and affect. Lonergan explicitly describes how feelings both prompt new questions and solidify our outlook through symbols, while Barrett describes affect as the foundation on which cognitive concepts label an experience (Theory of constructed emotion - Wikipedia). In effect, both say that what we feel influences what we think and expect, and vice versa, in a continually evolving loop.

To put it succinctly, Lonergan and Barrett converge on a view of the human being as a proactive meaning-maker. Our body-mind system is not a reactive sponge but an active constructor of reality: we anticipate and enact our world. Lonergan gives us the interior, introspective description of this (the transcendental movements of consciousness and the empowerment of authentic attentiveness, intelligence, reasonableness, responsibility) while Barrett gives us the empirical, neurological description (the brain’s predictive allostatic regulation and concept-driven emotion construction). Both perspectives will serve as a foundation for rethinking embodiment in what follows.

Embodiment as Predictive Intelligence: The Body–Mind as an Anticipatory Loop

Understanding humans as predictively embodied shifts our view of the body from a passive vessel to an active participant in cognition and identity. If Lonergan and Barrett are right, then our very perception, emotion, and thinking are thoroughly conditioned by continuous prediction, much of which is grounded in our bodily existence. The body (through brain-body neural circuits) is effectively enacting a “best guess” of the world at every moment – a process sometimes likened to “controlled hallucination” in cognitive science. This section will explore how embodiment itself functions as a kind of intelligence, aligning insights from cognitive science, phenomenology, and psychology.

From a cognitive science perspective, the ideas we’ve discussed align with the influential framework of Predictive Processing (PP) or Active Inference. As philosopher Andy Clark notes, predictive processing depicts perception and action as part of one inferential flow: the brain’s hierarchies constantly attempt to minimize prediction error by adjusting either their predictions or the body’s actions (The Mind-Expanding Ideas of Andy Clark | The New Yorker). This inherently blurs the line between “mind” and “body” – the brain’s predictions are not solipsistic guesses, they are about the body in the world and are tested through bodily movement and sensation. Clark emphasizes that mind, body, and world form a smoothly synchronized system in predictive processing, “continuously interacting” in largely unconscious ways (The Mind-Expanding Ideas of Andy Clark | The New Yorker). Notably, he and others argue this framework requires an embodied approach: cognition is fundamentally shaped by the particular structure of our animal body (The Mind-Expanding Ideas of Andy Clark | The New Yorker). For instance, our sensorimotor capacities (having two eyes, upright posture, opposable thumbs, a certain metabolic rate, etc.) dictate what and how we predict. The body is not a peripheral input device but a central component of the predictive mind. Neuroscientist Karl Friston’s work on active inference goes so far as to say that minimizing prediction error drives bodily action – the brain issues motor commands to make the world conform to its predictions, thus achieving its expected states (The Mind-Expanding Ideas of Andy Clark | The New Yorker). In simpler terms, if your body “predicts” that an object is graspable in a certain way, it will move your hand accordingly; if prediction and feedback align, you smoothly pick it up, if not, you fumble and the model updates. The body itself is an executor of predictions.

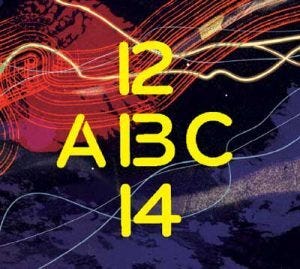

This tight perception–action loop is elegantly demonstrated by perceptual illusions. One striking example involves an ambiguous figure that can be read as a letter or a number depending on context. In the figure below, the same yellow shape appears in two sequences: amidst letters “A 13 C” it is seen as the letter B, but amidst numbers “12 13 14” it is seen as the number 13 ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). The image doesn’t change – your brain’s interpretation (and thus your visual experience) changes based on the predicted context. This optical illusion highlights how our brain uses prior knowledge and contextual cues to actively construct what we perceive ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). It literally anticipates whether it should see a letter or number and perceives accordingly – illustrating predictive embodiment in a simple sensory domain.

( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ) An ambiguous figure in context: when read in a letter sequence (“A _ C”), the central figure is perceived as “B”; in a number sequence (“12 _ 14”), the same shape is perceived as “13” ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ). The brain’s predictive context (letters vs. numbers) actively shapes what is seen. This demonstrates the mind’s role in constructing perception from ambiguous data, an example of predictive processing in action.

In everyday life, our predictive body-mind is doing far more complex feats. Consider walking down a flight of stairs in the dark: you anticipate each step through kinesthetic memory and proprioceptive feedback; if the last step is shorter than expected, you experience a jolt of surprise – your body literally predicted a step that wasn’t there. Or take the act of driving: experienced drivers often operate on “auto-pilot” because their sensorimotor system has internalized countless patterns and can predict traffic flows or the feel of the road, freeing their conscious mind to some degree. These instances show the body’s intelligence in action – an intelligence born of iterative prediction and correction.

From a phenomenological philosophy standpoint, thinkers like Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty long ago observed that conscious experience has an intrinsic temporal structure of retention (just-past) and protention (just-about-to-occur). In Husserl’s analysis of time-consciousness, every “now” moment is thick with the echo of what just happened and an anticipatory sense of what is next – a protention that is essentially a pre-reflective expectation of continuity. Merleau-Ponty, focusing on embodiment, showed that perception always implicates the unseen aspects of an object or environment as part of its meaning. For example, when I see a cube, I don’t actually see all its sides at once, but I anticipate the existence of a hidden face; my perception “transcends itself toward” that hidden aspect as if it were already co-present (Maurice Merleau-Ponty - Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). This implies that the unity of the perceived world is “lived” in anticipation before it is fully articulated by thought (The Vulgar Expression of Being: Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and other Abled Bodies – JHI Blog). As one commentator on Merleau-Ponty notes, “the unity of the world, before being posited by knowledge in a specific act of identification, is ‘lived’” – an experiential coherence held together by the body’s practical anticipation of stability. The upshot is that our bodily existence is oriented toward the future at the most basic level: to perceive at all is already to expect. Merleau-Ponty’s famous studies of motor intentionality (like the blind man’s cane becoming an extension of his body schema) further illustrate how the body incorporates tools and habituated actions to literally extend its predictive grip on the world. The cane enables the blind person to anticipate obstacles through feeling – the cane’s tap and vibration become predictions in the hand about the space ahead. Such phenomenological descriptions resonate strongly with today’s neuroscience of embodied prediction, providing a philosophical richness to the empirical model.

The concept of embodiment as predictive intelligence can be summed up in the phrase: the body learns and knows forward. Through repeated interaction, the body–brain system builds an implicit model of “how things normally go,” which allows it to both pre-plan actions and pre-perceive meanings. This enfolded knowledge could be compared to what Aristotle and Aquinas called habitus – ingrained dispositions or “second nature.” In moral philosophy, for instance, a virtue is seen as a habitus that makes certain good actions easy, prompt, and joyful, almost automatic, as if second-nature. Modern neuroscience might rephrase that as: a virtue is a beneficial predictive model for behavior (and feeling) that a person has cultivated. Indeed, Aquinas wrote that virtue is a habit “in the manner of nature” – once acquired it operates in us with the effortless anticipation of a natural reflex (Library : The Natural, the Connatural, and the Unnnatural | Catholic Culture). This is predictive embodiment in the ethical sphere: one’s body and affect have been trained so well that they intuitively anticipate the virtuous response in relevant situations (e.g. the compassionate person’s eyes may fill with tears before they even consciously decide to sympathize – their body “sees” suffering and responds).

Modern psychology and development offer plentiful examples of embodied predictive loops. Infants, for example, are little prediction machines: a baby learns that crying usually brings a caregiver, forming a primitive expectation; if caregivers are responsive, the infant’s body settles with a sense of safety; if not, the infant’s stress systems may remain on high alert. Developmental psychologists speak of internal working models of attachment – cognitive-affective schemas in a child that predict how others will respond and thus influence the child’s own behavior and emotion (Internal working model of attachment - Wikipedia). A securely attached toddler has an embodied expectation (“if I’m upset, Mom will comfort me”) that allows them to explore the world with confidence, whereas an anxiously attached child may anticipate inconsistency, leading to clinging or distress. These early embodied predictions can become self-fulfilling in relationships later: an adult who unconsciously expects rejection might behave defensively and sadly confirm those very experiences. The body (via autonomic arousal, posture, tone of voice) often carries this implicit expectation into interactions. By the same token, therapy and education can be seen as processes of updating predictive models. In exposure therapy for anxiety, for instance, a patient learns through repeated safe encounters that their catastrophic predictions do not come true, and their bodily fear responses gradually recalibrate. The brain’s predictions about interoceptive cues of anxiety (racing heart, etc.) get re-written – a pounding heart can eventually be interpreted as “not dangerous” and the person’s lived experience changes from panic to manageable excitement. Even simple biofeedback or mindfulness practices leverage prediction: by bringing conscious awareness to breathing or heart rate, people can learn to voluntarily modulate these normally automatic predictions, improving emotion regulation.

In sum, looking at evidence from cognitive science and lived experience, our embodiment itself can be understood as an anticipatory, adapting form of intelligence. We live in what philosopher Shaun Gallagher called a “body schema” – a preconscious map of posture and capacity that is constantly predicting and adjusting – and also within what Barrett might call a “body budget” – a predictive allocation of resources that shapes mood and thought. This perspective reinforces that mind and body are deeply entwined: the mind is emboldened by embodied predictions, and the body ‘thinks’ ahead through mental models. This prepares us to approach Pope John Paul II’s theological vision with a fresh lens: if our bodies are predictive, what do they reveal about who we are and are becoming?

Theological Depth: “The Body Reveals (and Predicts) the Person”

Saint John Paul II’s Theology of the Body (TOB) – a series of lectures delivered between 1979–1984 – is renowned for its personalistic affirmation that the human body has intrinsic meaning and dignity. A key dictum from TOB is that “the body expresses the person” or in another formulation, “the body reveals the person” (Original Solitude Part 2: The Sacrament of the Body) (The Body Reveals the Person). By this, JPII means that the human body, in its masculinity or femininity and through actions (especially self-giving love), makes visible the invisible reality of the person – the spiritual soul, the “I”. Our bodies are not mere shells or instruments; they are integral to our identity and vocation. He even calls the body “sacramental” in the sense that it is a sign that efficaciously communicates the person, much like a sacrament conveys grace. “The body reveals us, giving form to our innermost being and unique personality. Our bodies are sacramental – they make the invisible visible.”

Traditional interpretations of this teaching emphasize the transparency of the body to the person: e.g., through facial expressions, gestures, and above all the sexual union of husband and wife, the body manifests love and the personhood of the giver/receiver of that love. John Paul II roots this in the creation narrative: man and woman created in the image of God discover in the “spousal meaning of the body” a call to self-gift – through the body they reveal their personhood and their call to communion (The Body Reveals the Person). Thus, the body is not extrinsic to the self; it is the self in visible form. As one summary puts it, “The body is not extrinsic to the person: the body reveals the person”. This had profound implications for theological anthropology, ethics of sexuality, and human dignity.

Now, how does this resonate with, and get enriched by, the notion of predictive embodiment? We propose a complementary phrasing: “the body predicts the person.” This is not to replace John Paul’s wording but to elucidate an added dimension: the body not only shows who we are, it actively participates in the making of who we are by its continuous anticipation of experience. In theological terms, the body has a role in the ongoing revelation of the person across time, by virtue of these predictive, self-constituting processes.

Let’s unpack this in stages:

The Body’s Role in Personal Identity: Christian theology (especially in its Thomistic strain, which JPII follows) holds that the human soul is the form of the body – together they compose one being, the human person. Therefore, changes in the body (brain, hormones, sensations) are not just “happening to” an external thing; they intimately involve the person. The science of predictive processing, as we saw, suggests that our moment-to-moment sense of self is tied to the brain’s model of our body. Interestingly, some neuroscientists have begun linking interoception to the sense of self: e.g., a study in Nature (2023) found that bodily awareness correlates with first-person perspective in consciousness (First-person thought is associated with body awareness in daily life). Theology of the Body would add: this makes sense because embodiment is the God-given mode by which human persons exist and manifest. If our brain’s predictive conversation with our heart, lungs, and gut partly determines whether we feel safe, anxious, hungry, affectionate, etc., then our identity – “the kind of person we are” at a given moment – is being co-authored by these bodily conditions. In other words, the body is actively “writing” the story of the person through what it signals and prepares.

For example, someone with a calm and balanced body-budget (perhaps through secure attachments and practice of virtue) will tend to experience and display a stable, open personality – their body predictively dampens extreme stress responses, enabling the person to act with freedom and compassion. Another person with a chronically dysregulated body (perhaps due to trauma) might find their predictive circuits expect harm, leading to hypervigilance or impulsivity – their body anticipations constrain the self they can reveal to the world (often an anxious or aggressive demeanor). Pastoral theology might see in this the workings of original sin and wounded nature, but also the hope of healing grace which can “rewire” the heart (quite literally, through spiritual peace affecting the nervous system). Thus, when JPII says “the body reveals the person,” we can deepen that: it reveals not a static entity but a developing personal narrative, one that the body itself (with the mind) is constantly shaping. The predictive body reveals the person-in-process – the person who is becoming.

Incarnation and Sacramentality: Christianity is centered on the mystery of the Incarnation – God becoming embodied in Jesus Christ – and on the sacramental economy where material things (water, bread, wine, oil, human bodies in marriage) become bearers of spiritual grace. The idea of predictive embodiment can add a fascinating layer to our understanding of sacramental signs. If our bodies anticipate and respond in patterned ways, then sacramental rituals (which involve bodily actions and symbols) might work in part by engaging and reorienting those predictive patterns. Consider the liturgy: standing, kneeling, singing, sharing bread and wine – these repetitive embodied practices train our body-minds toward certain dispositions (reverence, penitence, communal openness). Over time, a believer’s body “learns” the faith in a way that doctrinal instruction alone cannot achieve. Theologically, one could say the Holy Spirit gradually divinizes the person, and from a human perspective this occurs by gradually shaping the embodied predictive loops – e.g., the peace that one feels in prayer might eventually become a trait, as the body comes to expect solace in turning to God, modifying stress responses and even neural pathways. We might recall Lonergan’s point that our consciousness can have a “mystical” orientation of interest – perhaps referring to our capacity for transcendent experiences. Through prayer, the body and brain’s predictive modeling of reality can shift: instead of seeing the world as random or hostile, a mystic’s embodied brain might literally predict grace and presence, perceiving the world as filled with God’s love. While speculative, this aligns with John Paul II’s insistence that the body is capable of “making visible the invisible, the spiritual and the divine” – classically referring to sexual love imaging the Trinity, but extensible to any way in which our embodied life manifests God’s life in us.

“The Body Predicts the Person” – Moral and Eschatological Meaning: If the body’s anticipatory activity helps form the person, there is a moral dimension: we are called to involve our bodies in our growth in virtue and holiness. John Paul II, in Veritatis Splendor and other writings, emphasized the unity of moral and physical: virtue isn’t just in the soul, it must be expressed in bodily action consistently. Our analysis suggests that as we choose good acts repeatedly, we don’t just reveal a virtuous person in those moments – we also gradually train our very flesh to expect and desire the good. The body, in a sense, begins to predict virtue, making it easier to continue doing good. Conversely, vice or sin can become “embodied” such that our passions and even neural reward circuits predictively push us toward the next fix or selfish choice. This gives a new appreciation of ascetic practices (fasting, restraint, bodily discipline): they are ways to interrupt unhealthy predictions (e.g., “I must have this pleasure now”) and re-condition the body to find freedom and satisfaction in higher goods. It resonates with St. Paul’s athletic metaphors (“I discipline my body…”) and with JPII’s TOB teaching on self-mastery as a prerequistite to true self-gift.

Additionally, Christian theology holds a hope in the resurrection of the body – that the person will be glorified, body and soul, in perfect unity with God. In that state, perhaps one could say the body will fully reveal and also perfectly express the person’s true identity as intended by God, with no discord between the body’s impulses and the soul’s love. Might we imagine that in the saintly or risen state, the predictive harmony between body and soul is complete – the body only anticipates good, and the person is fully free to be his/her true self? John Paul II’s personalism, influenced by thinkers like Saint Edith Stein and Thomistic thought, already understood the person as a psycho-physical-spiritual unity (Empathy, Insight and Objectivity: Edith Stein & Bernard Lonergan). The idea of predictive embodiment reinforces that unity: even the ephemeral flows of heartbeat and hormone are part of how the personal spirit operates. In theological perspective, nature and grace cooperate even at the level of cellular anticipation. God’s grace can calm a racing heart and grant a peace “beyond understanding,” showing how the divine interacts with our predictive bodily self – maybe akin to “grace building on nature” by elevating our embodied patterns of living.

In conclusion of this section, John Paul II’s statement that “the body reveals the person” can be expanded: the body not only statically reveals, but dynamically realizes the person through time. The body’s predictive engagement with the world is one way the person is continually disclosed – to others, to self, and to God. This perspective doesn’t contradict TOB; rather, it enriches it with the language of modern science and a process view of identity. It also humbles us: much of who we are at any given moment is being influenced by pre-conscious embodied processes. Yet, grace and conscious effort can shape those processes over time, aligning us more and more with the life of the spirit.

Practical and Ethical Implications: Predictive Embodiment in Relationships and Morality

If we accept that human beings are predictively embodied persons, this carries significant implications for how we relate ethically to ourselves and others. It challenges us to foster empathy with an understanding that each person’s experience is a construction influenced by their bodily state and history. It also reframes moral responsibility in terms of self-awareness and habituation, and highlights the deeply interpersonal nature of our predictive loops.

Empathy and Intersubjectivity: Empathy is the capacity to understand and share the feelings of another. Traditionally, one might think we infer others’ emotions by observing their facial expressions or behavior. But if emotions are predictive constructions, empathy might better be described as our brains trying to “run” a version of the other’s model. We pick up on another’s bodily cues (facial muscle tension, tone of voice, posture – all outward signs of their interoceptive state) and our brain uses our own embodiment to simulate what it predicts the other is feeling. This aligns with the concept of mirror neurons and embodied simulation in social cognition. Philosophers like Edith Stein argued that in true empathy, we don’t just see a face and deduce an emotion, we directly perceive the other as a person in pain or joy – we see their body as expressive of a soul (Empathy, Insight and Objectivity: Edith Stein & Bernard Lonergan). In Stein’s words, “through empathy I know the other to be a person because their being expresses itself to me… I perceive the person rather than physical signs… I perceive [the other’s] body as a lived body (Leib)… the body of a conscious ‘I’ that is just as much a subject as I am.” (Empathy, Insight and Objectivity: Edith Stein & Bernard Lonergan). This phenomenological description can be married with predictive embodiment: we grasp the other because our own embodied mind can mirror the state – our brain makes a prediction (“If my body showed those signs, I’d be feeling X”) and in feeling that, we experience the other’s state. Thus, empathy relies on our own interoceptive awareness and concepts. Someone with richer emotion concepts or finer interoceptive tuning may empathize more readily (they have more predictive templates to apply), whereas someone cut off from their own body or with a very different cultural background might struggle (“I don’t know what they’re feeling”). Realizing this can foster patience and better communication: if two people have mismatched predictive models (due to different life experiences), they might misconstrue each other’s feelings. We see this in cross-cultural interactions and even in gender differences in communication.

The ethical takeaway is that empathy can be cultivated by training our embodied predictions. Practices like mindfulness, as mentioned, heighten sensitivity to one’s own affective cues, which in turn may improve one’s ability to resonate with others. Moreover, simply learning about the diversity of emotional expression (through literature or cross-cultural education) gives our brain more “templates” to predict others’ inner states accurately rather than stereotyping. When John Paul II said the body has a “spousal meaning” – a capacity for self-gift and receiving the other – we can interpret that also at the level of empathy: our bodies are built to connect and “feel into” each other. Indeed, research in social neuroscience suggests that during deep connection, people’s physiology can synchronize (heart rates, hormonal rhythms). We literally co-regulate one another’s body budgets in loving relationships – for example, a hug or comforting tone can lower someone’s cortisol and tell their brain “you are safe, you can predict calm.” Thus, empathy is not purely a moral sentiment in the abstract; it is an embodied intersubjective event, where two predictive systems couple for a moment. Healthy relationships arguably depend on entraining positive predictions in each other – e.g., over years, spouses learn each other so well that just a glance or the squeeze of a hand can communicate volumes, their bodies predict each other’s moves in a graceful dance.

Moral Responsibility and Personal Growth: Does seeing ourselves as predictive biological organisms diminish free will or responsibility? To the contrary, it can deepen responsibility by showing us what we can and must control – namely, the shaping of our habits, environments, and attention. We may not choose our momentary feelings directly (they often arise from unconscious predictions), but we are responsible for the long-term cultivation of our predictive patterns. This aligns well with classical virtue ethics. For example, a person may not be culpable for the flash of anger they feel (their body might automatically predict threat in a situation due to past trauma), but they are responsible for how they then act and for working to heal or reframe the underlying model if it consistently leads them astray. Lonergan spoke of the need for “conversion” – intellectual, moral, and religious – which entails actively uncovering and overcoming biases in our view and values. Many biases are essentially bad predictions or mis-calibrated expectations (prejudices are expecting a person to behave a certain negative way without real warrant; egotism is the persistent prediction that “I come first”; despair is the prediction “no good outcome is possible”). Correcting these involves insight (a new way of understanding) but also affective reorientation – changing the feeling-tone associated with certain ideas or groups of people. This typically requires experience: exposing oneself to counter-stereotypical examples, practicing generosity and seeing its fruit, etc., so that one’s embodied expectations shift. Thus, moral growth might be described as the process of training our embodied predictions toward the true and good. Parents and educators do this all the time: a good parent provides an environment that predictably rewards honesty and gently discourages dishonesty, so the child’s brain-body learns “truth-telling feels right (and is less stressful than lying)”. Over time, doing good becomes second-nature – the body “wants” it. This doesn’t remove the role of grace or the will, but it grounds those in the realistic context of psychology and neuroscience.

There is also a humbling ethical implication: if people’s outward behavior is mediated by their internal predictive state, we should show compassion and not rush to judgment. A normally kind friend snapping at you might be doing so because their body budget is depleted (perhaps they are hungry, tired, or in pain – their brain predicts irritability). While that doesn’t excuse wrongdoing, it contextualizes it and suggests paths for remediation (maybe what they need is rest and care, not punishment). Similarly in mental health – conditions like anxiety, depression, PTSD can be seen as “locked-in” predictive patterns (e.g., the body constantly predicts danger in PTSD, leading to hyperarousal and flashbacks). Knowing this, we can be more empathetic to those who struggle, realizing their very perception of reality is being skewed by these embodied expectations. It shifts moral language from blame to healing: how can we help re-train the person’s predictions so they can flourish?

Interpersonal Relationships and Community: Humans are social beings, and our predictive minds are heavily shaped by social interactions. As noted, attachments in early life set templates that often persist. In communities, collective expectations form a culture. This has ethical ramifications. For one, it suggests that to change a toxic culture, one must alter the shared habitual expectations, not just issue new rules. If a workplace has a culture of fear, everyone’s body might be in a state of heightened threat-prediction (stomach knots when the boss walks in, etc.). Overcoming that might require consistent transparency and positive reinforcement so that gradually bodies unlearn the fear response. On a more positive note, communities can be powerful sources of positive predictive embodiment. Think of chanting or dancing in unison – people report feeling “as one body,” which likely comes from all brains aligning their predictions (knowing the next beat or move) and thus creating a strong social bond. In faith communities, rituals and moral practices done together (like service to the poor) build a shared body of experience that shapes each member’s identity. There’s also an inherent call for solidarity: if I know my neighbor’s experience of the world is partly a function of how we treat each other, I have a responsibility to contribute to an environment that helps others form healthy, hopeful predictions. Something as simple as a smile or a kind word might, in predictive brain terms, nudge someone’s interoceptive model from “nobody cares about me” toward “maybe I am safe and valued.” In this sense, each of us is a factor in others’ embodied reality. John Paul II’s personalist ethic always insisted on the “communion of persons”, that we find ourselves only in sincere self-gift. Now we can say: when we give of ourselves kindly, we might literally be regulating someone’s nervous system toward peace. This casts love of neighbor in a fascinating neurobiological light – as participation in the maintenance of each other’s body budgets and emotional equilibrium.

Case Examples: To ground these ideas, let’s briefly consider a few concrete scenarios:

Educational Context: A teacher notices that a student often appears anxious and cannot concentrate. Instead of scolding him for lack of attention, the teacher employs an understanding of predictive embodiment. She realizes the student’s body may be stuck in a high-alert mode (perhaps due to stress at home, his brain predicts threat everywhere). She introduces a short breathing exercise at the start of class each day and maintains a very predictable classroom routine. Over weeks, the student’s body begins to expect calm in the classroom; his heart rate reduces when he enters this now-familiar safe space. Consequently, his ability to learn improves. This demonstrates how altering environmental predictability and using the body (breath, posture) can ethically support someone’s development. The teacher essentially helped rewire the student’s embodied predictions, an act of pedagogical empathy.

Therapy and Human Development: Consider a middle-aged man struggling with anger outbursts toward his family. Through counseling, he discovers that his angry reactions are often preceded by physical signs (heat in his face, rapid heartbeat) that he used to ignore until he “exploded.” These physical cues were his body’s predictive response to certain triggers (e.g., feeling disrespected, which unconsciously predicted a flashback of how his father treated him). The therapist works with him to become aware of those cues as predictions, not inevitabilities. By breathing, stepping away briefly, and reinterpreting the trigger (e.g., “my son is not attacking me, he’s just being a teenager”), the man gradually retrains his response. His family also learns to communicate in ways that don’t accidentally set off his alarm bells. Over time, not only do his outbursts decrease, but his underlying body state changes – he reports that situations which before would raise his blood pressure no longer do. This is a case of moral growth via predictive recalibration, benefiting relationships.

Pastoral/Theological Context: In a church setting, a community that understands predictive embodiment might incorporate practices that engage the body in spiritual formation. For example, a parish might host trauma-informed yoga or tai chi sessions in its hall, recognizing that bodily healing can be part of spiritual healing. A young woman who has experienced trauma may find it hard to feel God’s love because her body perpetually predicts danger and shame. Through gentle movement and prayerful meditation, she slowly experiences moments of safety in her body. Pairing those moments with spiritual reflection (like feeling held by God while in a relaxed pose), over months, allows her to start trusting again. In theological terms, her body was “remembering” Good Friday constantly; now it is learning Easter. The body predicting the person here means her bodily rewiring opens her heart to grace, and she emerges more confident in her identity as a beloved child of God. This illustrates how theology and pastoral care can integrate an understanding of embodiment deeply: the salvation and sanctification of the person include the calibration of their predictive physiology toward truth and love.

Conclusion

We have journeyed through an ambitious integration of ideas, from Lonergan’s cognitional philosophy and Barrett’s affective neuroscience to John Paul II’s theology, to argue for a unified insight: human embodiment is fundamentally predictive and this fact enriches our understanding of personhood. Far from being mere philosophical jargon or scientific esoterica, this synthesis has practical consequences for how we live, love, and grow.

Experience is inherently predictive – our minds continuously anticipate the world, and our bodies are active participants in this expectancy. By viewing Lonergan’s levels of knowing through the lens of Barrett’s predictive brain, we see that even our most spiritual or abstract strivings (for truth, for God) are grounded in a nature that learns by guessing and adjusting. Conversely, Barrett’s claims find a larger meaning when placed in Lonergan’s and JPII’s personalist context: the fact that my brain issues interoceptive predictions and constructs my feelings doesn’t make me a machine; it is part of how my personal self emerges and acts in the world – through a constant loop of sensing, meaning-making, and responding, all of which involve my incarnate being.

The hypothesis stated at the outset was that the body actively anticipates and constructs personal identity through a cognitive-affective loop. We have seen multiple angles of support for this. Lonergan taught us that the subject is an agent of inquiry and value, with feelings operating as vectors in the loop of consciousness. Barrett showed us the nuts and bolts of that loop in the brain, with interoceptive predictions giving rise to affect, which then calls for conceptual interpretation. John Paul II reminded us that this entire drama is meaningful: it is the person coming to be, and the body is the protagonist alongside the soul in the drama.

Reframing JPII’s aphorism “the body reveals the person” as “the body predicts the person” is a way of saying that embodiment is not just a static sign of who we are, but an active process that helps determine who we become. Our bodies “whisper” to us with feelings and impulses – not infallibly, sometimes misleadingly – but if we listen and educate those whispers, they can guide us to genuine self-understanding and moral living. In a sense, the body “prophesies” the person: it generates signals and trajectories of action that, over time, manifest as character and identity.

This interdisciplinary exploration also highlights a beautiful consonance between science and religion on the point of human unity. Both Barrett’s research and Theology of the Body reject a mind–body dualism. They imply a holistic view of the human being: networks of neurons and hormones are, in their own register, doing the work that spiritual and personal development describes in another. There is a profundity in our flesh. As the Psalmist wrote, “I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” The science of predictive processing gives us a glimpse of that wonder in the fine design by which we adapt to our world; theology gives it ultimate meaning by situating that design in God’s plan for loving communion.

In practical terms, embracing predictive embodiment should foster humility, compassion, and hope. Humility, because we recognize much of what we experience or even do is driven by pre-conscious patterns – we are not as in control or as purely rational as we might think. Compassion, because when others err or suffer, we can see they might be “trapped” in bodily cycles that they did not fully choose – and thus we approach them with care and a desire to understand the story written in their flesh. And hope, because predictive models can change – neurons can rewire, hearts can be re-conditioned, and with support and grace, people can overcome what once seemed like “nature.” In fact, the very plasticity of our predictive mind is what underlies conversion and growth: we are not stuck being the person our past wrote into our body; we can, with effort and grace, become someone new. The body can learn to predict redemption instead of repetition.

Finally, this synthesis invites further questions and research. How might pastoral counselors incorporate interoceptive training in spiritual direction? Could Lonergan’s method help science remain attentive to values in investigating the mind? Are there limits to using neuroscience to explain theological truths? These are fertile areas for dialogue. But what seems clear is that when disciplines converse, our understanding of ourselves deepens. The mystery of embodiment – of being incarnate spirits – is too rich for one field alone. As we have seen, Bernard Lonergan’s philosophical acumen, Lisa Feldman Barrett’s scientific rigor, and John Paul II’s theological vision each illuminate different facets of this mystery. Together, they help us appreciate the human person as an embodied spirit who lives in a constant dialectic of prediction and surprise, need and fulfillment, action and meaning. In that dynamic dance, we find the hand of Providence and the call to communion. The body reveals the person, the person reveals God (in whose image we are made), and perhaps, in the gentle depths of our physiology, God’s wisdom is at work – teaching our hearts when to leap and when to rest, training our being for love.

Such an integrated view of predictive embodiment not only satisfies an intellectual curiosity but can fundamentally enrich the way we see ourselves and treat one another – as creatures wonderfully made, navigating life through the wisdom of our bodies and the freedom of our souls, always oriented toward a future we are co-creating with every breath and every heartbeat.

References:

Bernard J.F. Lonergan, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding (1957); Method in Theology (1972).

Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain (2017); Barrett & W.K. Simmons, “Interoceptive predictions in the brain,” Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16(7):419-429 (Interoceptive predictions in the brain - PubMed) (Interoceptive predictions in the brain - PubMed).

Pope John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body (collection of Wednesday audiences, 1979–84) (The Body Reveals the Person).

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Lonergan (Lonergan, Bernard | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) (Lonergan, Bernard | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

Wikipedia – “Theory of Constructed Emotion” (Theory of constructed emotion - Wikipedia) (Theory of constructed emotion - Wikipedia).

Edith Stein (St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross), On the Problem of Empathy (1917) as discussed in Sobrak-Seaton, “Empathy as Perception of Psycho-Physical-Spiritual Unity” (Empathy, Insight and Objectivity: Edith Stein & Bernard Lonergan).

Andy Clark, Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind (2016); New Yorker article on Clark (The Mind-Expanding Ideas of Andy Clark | The New Yorker) (The Mind-Expanding Ideas of Andy Clark | The New Yorker).

Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (1945) (The Vulgar Expression of Being: Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and other Abled Bodies – JHI Blog).

Lisa Feldman Barrett, Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain (2020) – on allostasis ( Interoception: The Secret Ingredient - PMC ).

J. Bowlby, Attachment and Loss (1969) – on internal working models (Internal working model of attachment - Wikipedia).